My Story

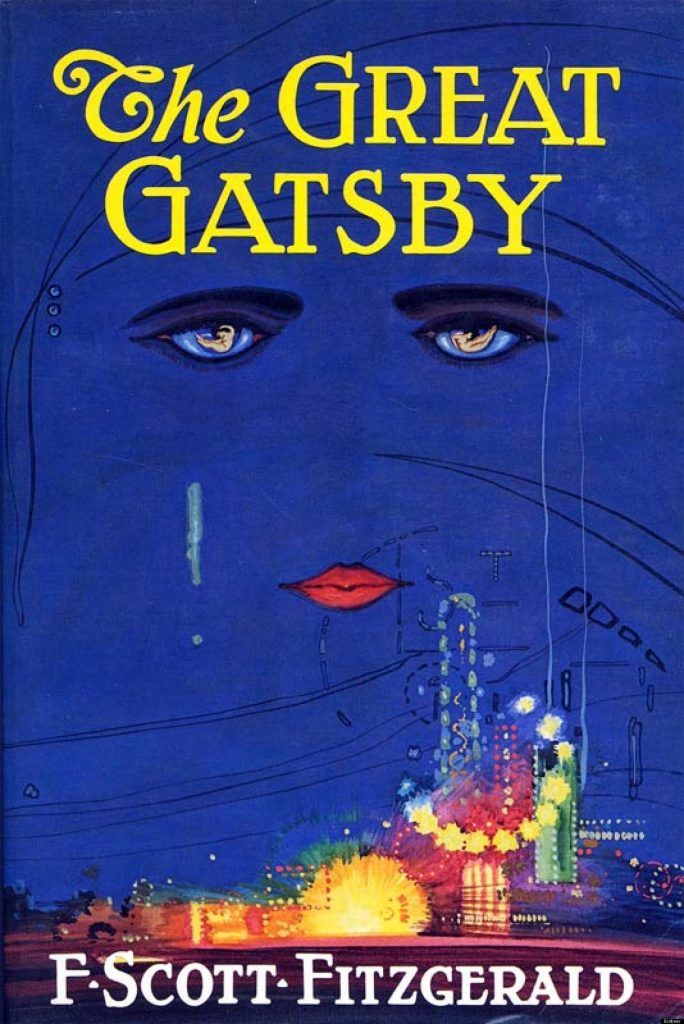

I knew nothing about Isherwood at the time, and had even missed the film 'Cabaret', which is inspired by the stories. I had gotten the book at the station in Utrecht, as a gift from a friend, and when I crossed the border at Oldenzaal, I read how Isherwood's alter ego crossed the same border on the way to a large, dangerous city and romantic adventures.

I went to Berlin to do historical research in an East German archive. I also lived for six months in the communist part of the city, which at the time looked much more than the Western side, like Isherwood's Berlin from the 1930s. Traveling on the rattling S-Bahn and strolling through dilapidated neighborhoods like Prenzlauer Berg, it took little effort to imagine the modern equivalents of Isherwood's landlady Miss Schoeder, or the charming con man Mr. Norris, and the faileded femme fatale Sally Bowles. Because Isherwood had drawn me so smoothly, without my noticing, into his grotesque world, it seemed very natural to me that I would meet similar figures. And could write about it. That was the most important revelation: that you can write with humor and empathy about unimportant people, a stranger you meet on the train (Mr. Norris), your landlord (Miss Schoeder), an accidental acquaintance (Sally.) In history. (my profession at the time) they don't play a role, but if you write about them well, like Isherwood, they live much longer than the average dissertation.

I am deeply indebted to Isherwood. My very first short story 'The house at the Kollwitzplatz' (Maatstaf, 1982) and my first novel 'Käte Jahn' (1991) are directly inspired by his work and take place in the demi-monde of communism. If I had known anything about Isherwood's life, or had read his autobiography 'Christopher and his kind', it would probably all have turned out very differently.

I literally believed Isherwood when he wrote, 'I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive.' I spontaneously fell in love with the idea of the stranger, the distant observer who only gets involved, against his will, when disaster strikes. Isherwood spontaneously fell in love with boys. In the autobiography he writes: 'Berlin meant boys.' He led a very active sex and love life, sometimes together with his friend the poet Wystan Auden, but in the 1930s he could not write about it honestly, or maybe I should say, literally. So he came up with a very curious alter ego, an almost abstract, asexual figure, so passive that he really consists only of the witty things he says in conversation. In 'On Ruegen Island', about a beach vacation with his very young boyfriend Otto, he even splits himself in two, which made the story completely incomprehensible to me.

Did I misunderstand 'The Berlin Stories' the time I read the book? Without a doubt. It seems to me a perfect example of 'misreading', a term the American critic Harold Bloom uses to analyze the mechanics of a literary tradition. All writers start out by imitating predecessors they admire, but they read those predecessors without realizing it in a personal, "wrong" way. Only through 'misreading' can they, if they are good, rise above the influence of those predecessors.

This may sound like a plea against reading (and writing) biographies, but it is not meant to be. It was a stupid and happy coincidence that I was cluweless while traaveling on the train with Isherwood at an important moment in my life. Since then I have read everything by and about Isherwood, and learned a lot from it. Particularly instructive is his lifelong struggle with the ‘I', the first person narrator. It is a cliché that all literature is autobiographical, but for Isherwood it is true with a vengeance. He wrote his first autobiography when he was only thirty-four (Lions and shadows, 1938), and used the same material in the more candid novel 'Down there on a visit' (1962). His other novels (Prater Violet, 1945, and A Single Man, 1964) are also barely concealed chapters of his own life. He kept a very detailed diary for nearly sixty years, and in the end redid the autobiography on a large scale (Christopher and his kind, 1977). In the last autobiography, in an almost desperate attempt to tell all those different versions of his life apart, he wrote about himself in third person. The aforementioned quote is in full: 'For Christopher, Berlin meant boys'.

I've been writing exclusively fiction for years now and know that if your narrator is not a fictional character, you will inevitably get yourself into trouble. I think this explains why 'The Berlin Stories' is Isherwood's best and most widely read book. The constraints of the time prevented him from writing about his own experience, and he had to come up with a narrator. This figure, the mysterious, passive observer who does not reveal anything about himself, and whom you nevertheless eagerly follow to the seamy side of Berlin, is Isherwood's most original and intriguing creation.

Wilt u mij uitnodigen voor een lezing of optreden? Neem contact op met mijn literair agent Dorine Holman. Zij kan u nader informeren over de mogelijkheden.

We nemen zo snel mogelijk contact met u op.

Probeer het later nog eens.